Ben has cerebral palsy that affects his entire body. He cannot sit, stand, speak or walk. But he is bright, alert and knows what is on his mind.

When I adopted Ben at age three, he could only communicate using eye gaze and a slight nod for ‘YES’ and a quick glance to the left for ‘NO’. It was sometimes difficult to detect which answer he was giving to questions.

Here is Ben with the words ‘YES’ and ‘NO’ on his wheelchair tray. With the words present, it made understanding more accurate.

Here is Ben with the words ‘YES’ and ‘NO’ on his wheelchair tray. With the words present, it made understanding more accurate.

As Ben became more proficient we added more symbols to his tray. Here you can see a couple more: bathroom, drawings to communicate if he wanted his head light on or off. He is using eye gaze in this photo to indicate what he wants to say.

As Ben became more proficient we added more symbols to his tray. Here you can see a couple more: bathroom, drawings to communicate if he wanted his head light on or off. He is using eye gaze in this photo to indicate what he wants to say.

In this picture Ben is attempting to use gross motor skills by placing his fisted hand on the circles on his tray. In the circles are drawings illustrating classifications: foods, activities, people, animals, etc. These allowed Ben to indicate more expanded thoughts about what he wanted. It was still a guessing game of the person communicating asking YES/NO questions and then more specific questions such as, “Do you want to eat a hamburger?” and wait for an answer from Ben. I covered all these pictures with clear contact paper to protect them from dirt, water, and whatever else would come in contact with his wheelchair tray.

In this picture Ben is attempting to use gross motor skills by placing his fisted hand on the circles on his tray. In the circles are drawings illustrating classifications: foods, activities, people, animals, etc. These allowed Ben to indicate more expanded thoughts about what he wanted. It was still a guessing game of the person communicating asking YES/NO questions and then more specific questions such as, “Do you want to eat a hamburger?” and wait for an answer from Ben. I covered all these pictures with clear contact paper to protect them from dirt, water, and whatever else would come in contact with his wheelchair tray.

We made a rather crude piece of headgear with a flashlight attached to allow him to keep his head up when communicating. It also was easier than simply following his eye gaze when he would shine the light on objects or icons on his easel board. This was created out of a couple pieces of leather, elastic, Velcro and some foam to help keep it from rubbing under his chin.

We made a rather crude piece of headgear with a flashlight attached to allow him to keep his head up when communicating. It also was easier than simply following his eye gaze when he would shine the light on objects or icons on his easel board. This was created out of a couple pieces of leather, elastic, Velcro and some foam to help keep it from rubbing under his chin.

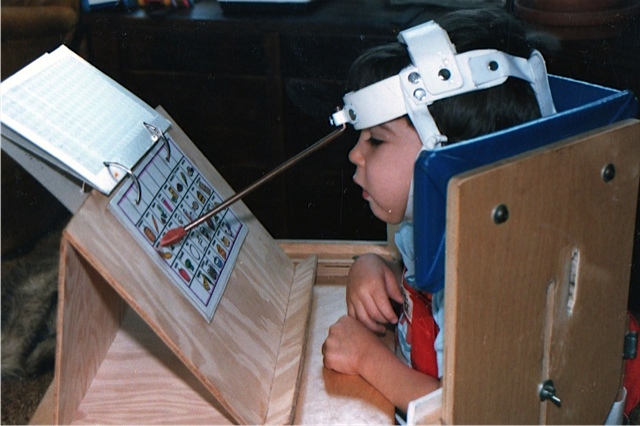

Ben’s intelligence and quick understanding of icons kept us trying to create faster and more accurate methods for him to communicate. My dad made him this easel and I made several classification sheets with small icons. We then constructed this head pointing stick to show us which icon he wanted to use. As great as it looks in this picture, it wasn’t all that great when actually trying to use it because of limited range of his head movements. For example, he could reach the upper two rows of icons but not the bottom two rows unless someone moved the easel back and forth.

Ben’s intelligence and quick understanding of icons kept us trying to create faster and more accurate methods for him to communicate. My dad made him this easel and I made several classification sheets with small icons. We then constructed this head pointing stick to show us which icon he wanted to use. As great as it looks in this picture, it wasn’t all that great when actually trying to use it because of limited range of his head movements. For example, he could reach the upper two rows of icons but not the bottom two rows unless someone moved the easel back and forth.

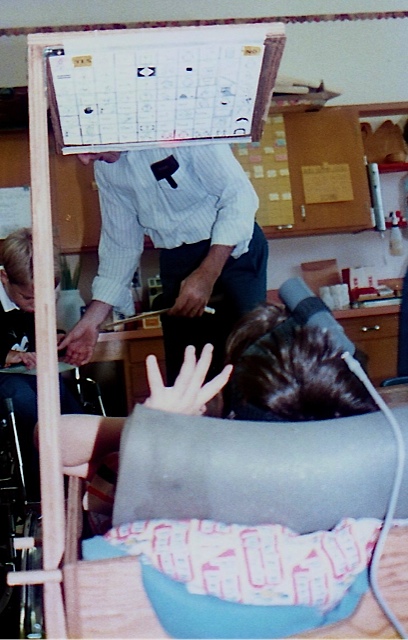

Ben needed to have hip surgery and was in a large spica cast for a long period of time. This prevented him from being able to sit upright in his wheelchair. His teacher helped to develop this communication board that he could use with his light pointer. The long arm was adjustable and could be dropped down when he was placed on his stomach.

Ben needed to have hip surgery and was in a large spica cast for a long period of time. This prevented him from being able to sit upright in his wheelchair. His teacher helped to develop this communication board that he could use with his light pointer. The long arm was adjustable and could be dropped down when he was placed on his stomach.

The board could be raised up when he was placed on his back. It was rather tricky for people to see the board when he was on his back. In other words, we had to squat down to see the icons.

The board could be raised up when he was placed on his back. It was rather tricky for people to see the board when he was on his back. In other words, we had to squat down to see the icons.

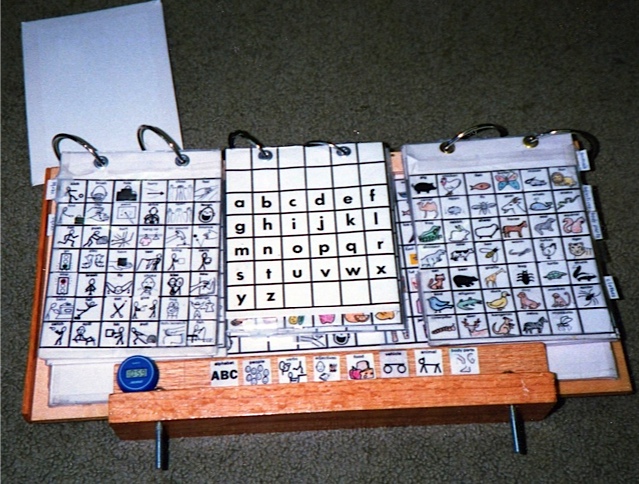

After Ben’s surgery and he was back in his wheelchair, I developed this larger communication board, which he used with his light pointer. The posts on his tray helped him to keep his trunk upright and to make his head steadier to control his light. The sheet that is shown here allowed Ben to construct complete sentences/questions by pointing his light on one icon at a time. The icons were arranged in noun/pronoun, verb (present-past), prepositions, adjectives, and noun order. I made several of these larger sheets which slid in and out behind each other and could be used in his various mainstreamed classes: science, language arts, social studies, etc.

After Ben’s surgery and he was back in his wheelchair, I developed this larger communication board, which he used with his light pointer. The posts on his tray helped him to keep his trunk upright and to make his head steadier to control his light. The sheet that is shown here allowed Ben to construct complete sentences/questions by pointing his light on one icon at a time. The icons were arranged in noun/pronoun, verb (present-past), prepositions, adjectives, and noun order. I made several of these larger sheets which slid in and out behind each other and could be used in his various mainstreamed classes: science, language arts, social studies, etc.

This is the same board with the flip sheets made available. The icons on the sheets were arranged by categories.

This is the same board with the flip sheets made available. The icons on the sheets were arranged by categories.

This is a close up of the board. You will notice Ben’s little blue watch stuck on there so he could tell time. He insisted this be placed where he could see it at all times. Then you will see various icons along the bottom on the wood frame. He would point his light on specific icons to let us know which page to flip to – alphabet, people, verbs, foods, etc. Ben had over 600 icons on this board and he made good use of them. Of course there were drawbacks: the listener needed to stand behind Ben to see where the light was being pointed. The listener had to break eye contact when standing behind Ben. Someone had to be able-bodied to flip the sheets and there was no voice. However, the benefits outweighed the drawbacks – Ben could communicate and we could see he was able to develop complex sentences, ask questions, and spell.

This is a close up of the board. You will notice Ben’s little blue watch stuck on there so he could tell time. He insisted this be placed where he could see it at all times. Then you will see various icons along the bottom on the wood frame. He would point his light on specific icons to let us know which page to flip to – alphabet, people, verbs, foods, etc. Ben had over 600 icons on this board and he made good use of them. Of course there were drawbacks: the listener needed to stand behind Ben to see where the light was being pointed. The listener had to break eye contact when standing behind Ben. Someone had to be able-bodied to flip the sheets and there was no voice. However, the benefits outweighed the drawbacks – Ben could communicate and we could see he was able to develop complex sentences, ask questions, and spell.